Patriotism in the Street

Section 7

Philadelphians came together publicly to show support for the war effort. From attending war bond rallies to participating in patriotic sing-a-longs to watching parades, Philadelphia residents honored those who were serving and encouraged the city to do whatever it could to help win the war.

“A solid seething mass of humanity stacked shoulder to shoulder as far as you could see was jammed in the streets. I can still hear my father swearing, pulling my mother through the crowds, and she, near tears, pulling me. It seemed everyone in the city was jammed into the City Hall area in all directions.”

Morris G. Condon III recalling Philadelphia’s Armistice celebration

First News of Peace!, November 11, 1918. Gelatin silver photograph.

The Liberty statue became Philadelphia’s focal point of celebration when news of the armistice reached the city. Philadelphia’s mayor declared a civic holiday. “Business stops, while every man, woman and child joins in rejoicing” declared the Philadelphia Inquirer’s front page headline.

28th Division Parade Passing Independence Hall, May 15, 1919. Gelatin silver photograph.

Over two million people watched the 28th Division troops (nicknamed the Keystone Division) parade through city streets upon their return from the war. Pennsylvania’s governor, the city’s mayor, and other dignitaries sat in reviewing stands opposite Independence Hall. At four points along the eight-mile parade route, including the Library Company’s building on South Broad Street, thousands of schoolchildren assembled to wave flags and cheer the soldiers.

Officers of the Emergency Aid on Parade, ca. 1918. Gelatin silver photograph.

The Emergency Aid of Pennsylvania was one of numerous relief organizations founded by women to assist the war effort. Philadelphia’s branch included women from some of the city’s most prominent families. This organization raised money for the relief of America’s European allies. Once America entered the war, the organization sent medical supplies, clothing, tobacco, candy, and other treats overseas to the troops, sold war bonds, and supported local wartime industries. Here members of the Emergency Aid march in a parade along the north side of Philadelphia’s City Hall.

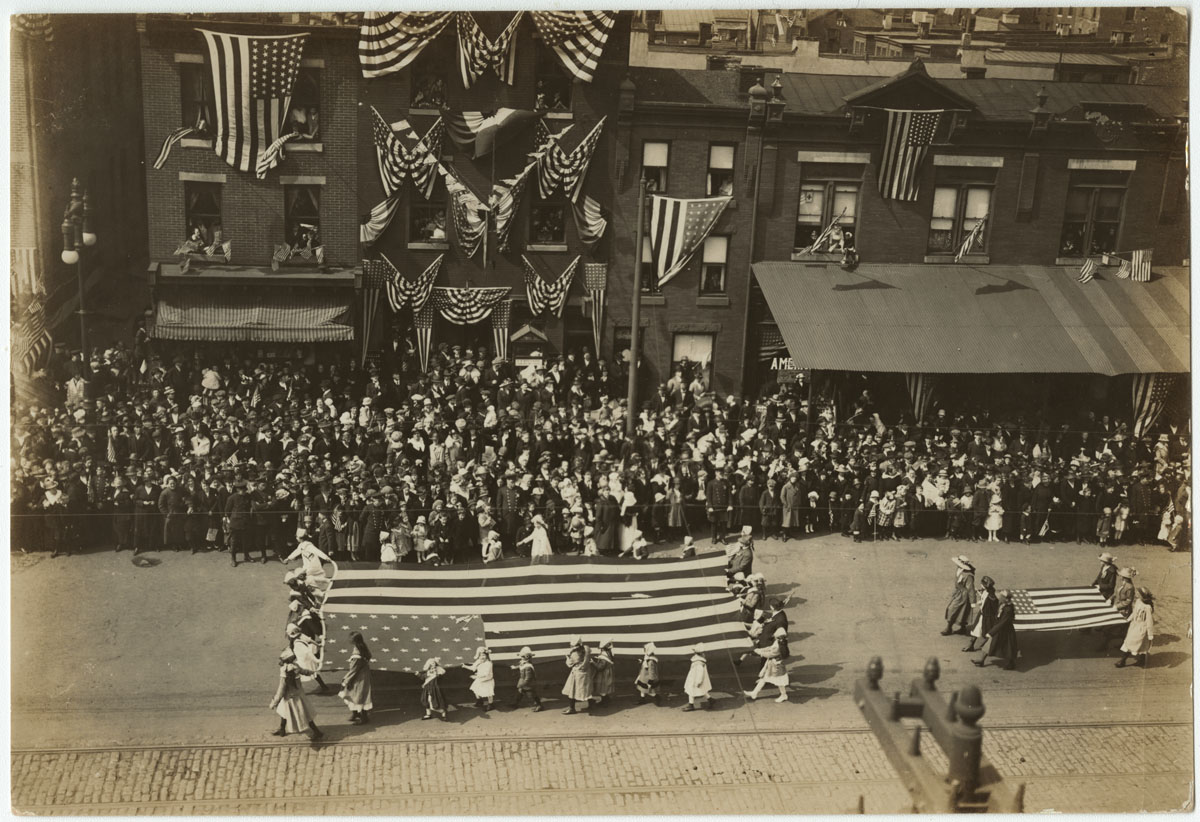

Liberty Loan Parade, 1200 block of Montgomery Avenue, April 6, 1918. Gelatin silver photograph.

Patriotic celebrations were not confined to Center City. To kick off the Third Liberty Loan drive and commemorate the one-year anniversary of America’s entrance into the war, 5,000 adults and 1,500 children marched through the streets of Kensington. Flag-waving crowds lined the sidewalks and leaned out of windows. Notice the Red Cross Service Flag in the second floor window on the right.

Floats in Red Cross Parade to Aid Big Drive for Membership, possibly June 22, 1917. Gelatin silver photograph.

Once America entered the war, membership in the Red Cross grew tremendously. During one week in June of 1917, Philadelphia’s Red Cross chapter endeavored to raise three million dollars to support their extensive charitable work. Unlike many other parades, this membership drive parade traveled down North Broad Street in front of largely silent crowds, who according to the Philadelphia Inquirer “contemplated the seamy side of the struggle the country has been forced to enter.”