Food Will Win the War

Section 4

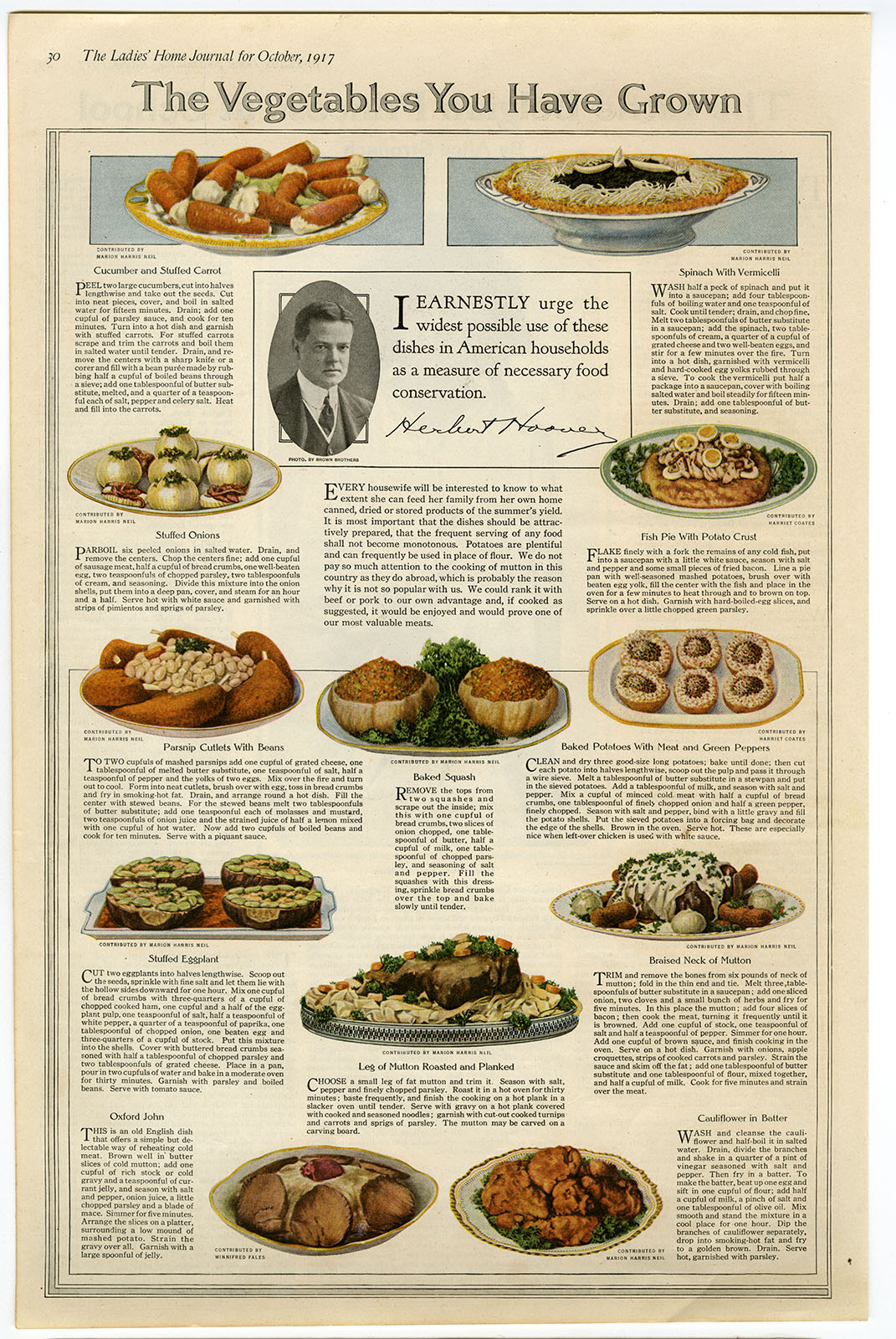

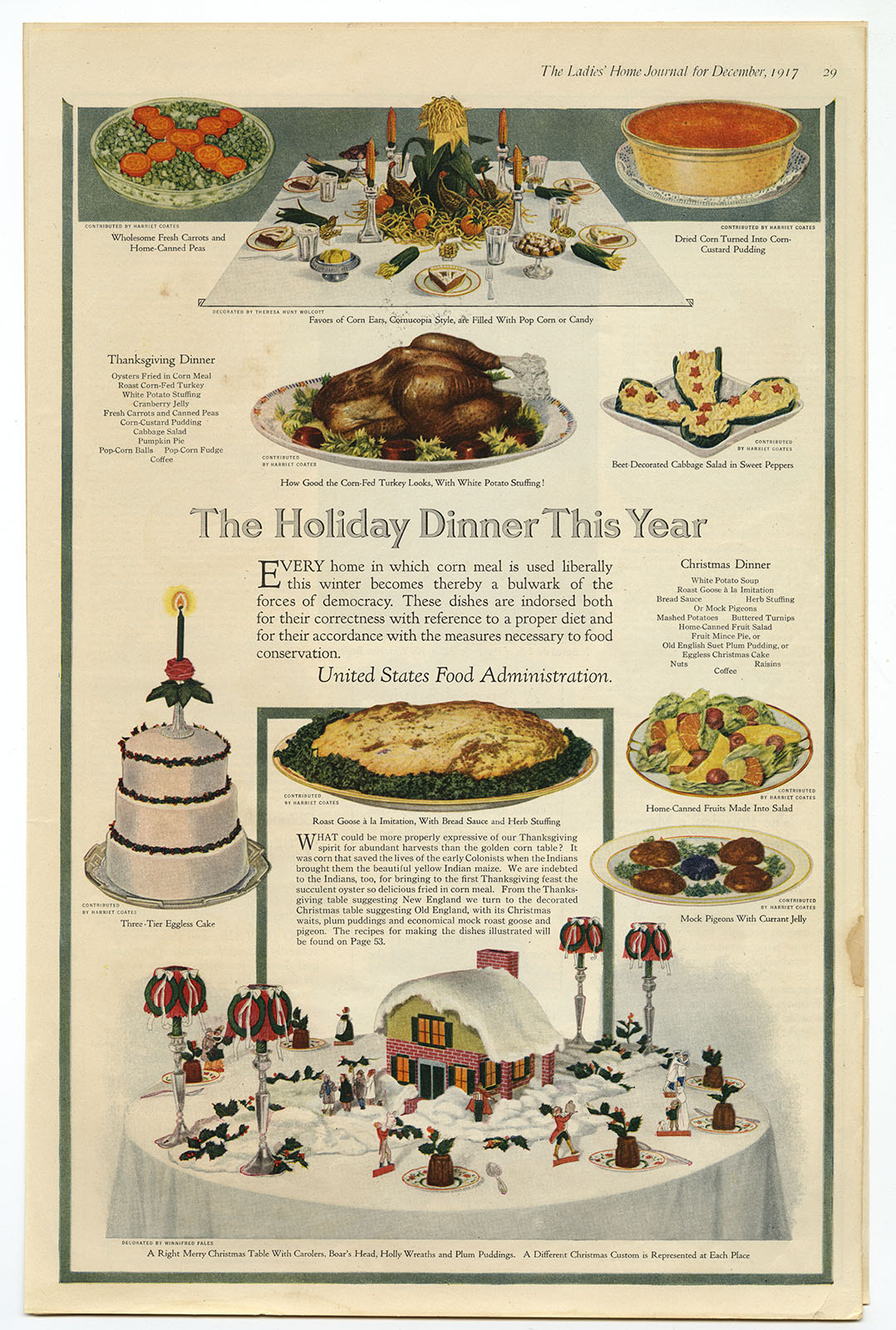

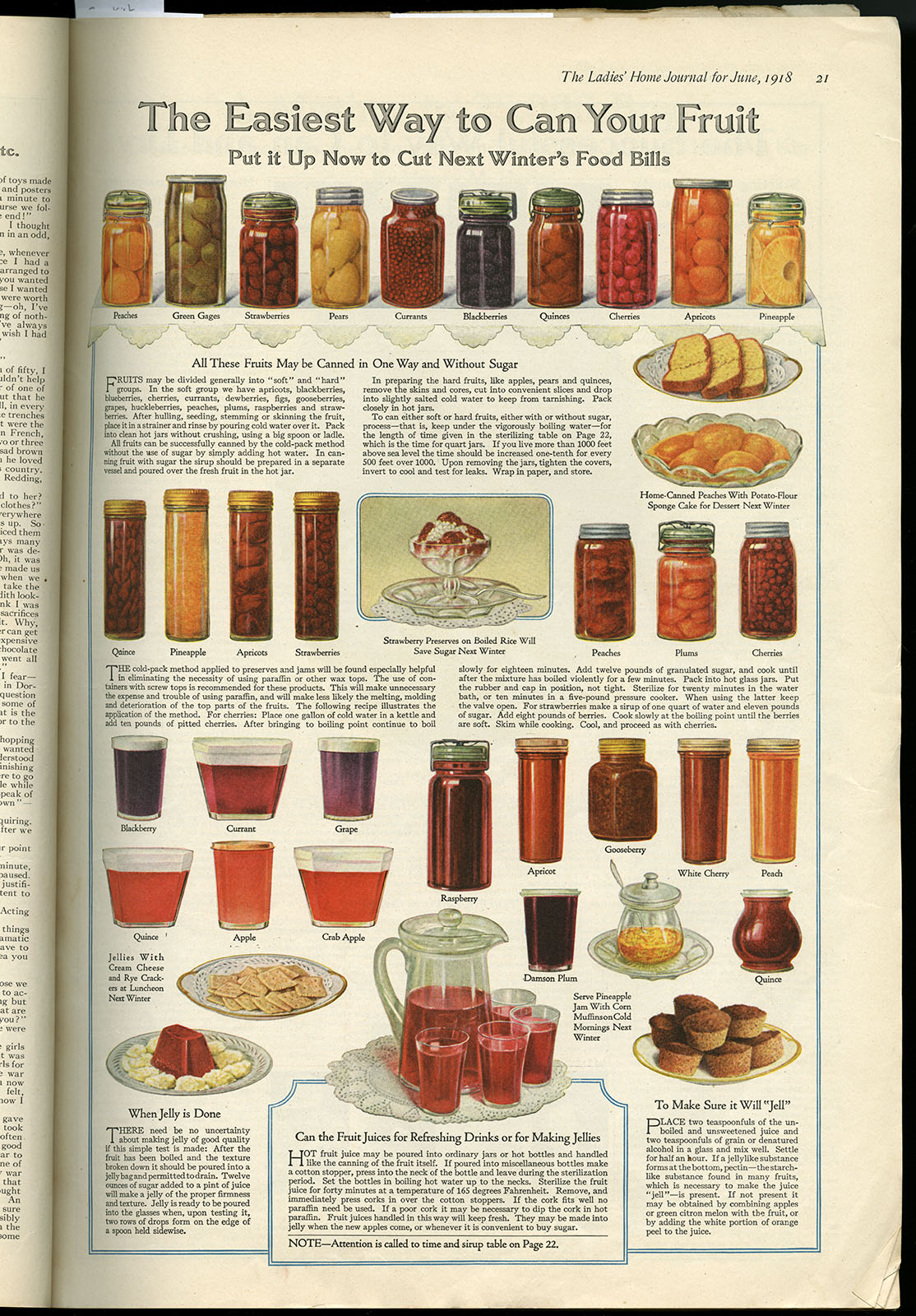

Eat local, meatless Mondays, go wheatless, more fruits and vegetables, less white sugar— many of the things we hear a lot about today Americans did during the First World War. The United States Food Administration, created in 1917 and headed by Herbert Hoover, campaigned to convince Americans to voluntarily change their eating habits in order to have enough food to feed our military and starving civilians in Europe. This included conserving wheat, meat, sugar, and fats, so those items could be sent overseas. The Administration advocated using alternatives like honey or molasses for sugar and corn or barley for wheat. They educated with memorable slogans, such as “when in doubt, eat potatoes” and “help us observe the Gospel of the clean plate” and invented “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays.” To free up transportation for war supplies, they encouraged buying locally produced food, or better still, growing liberty gardens.

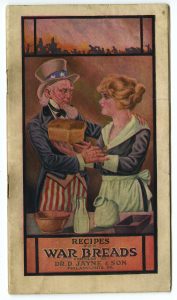

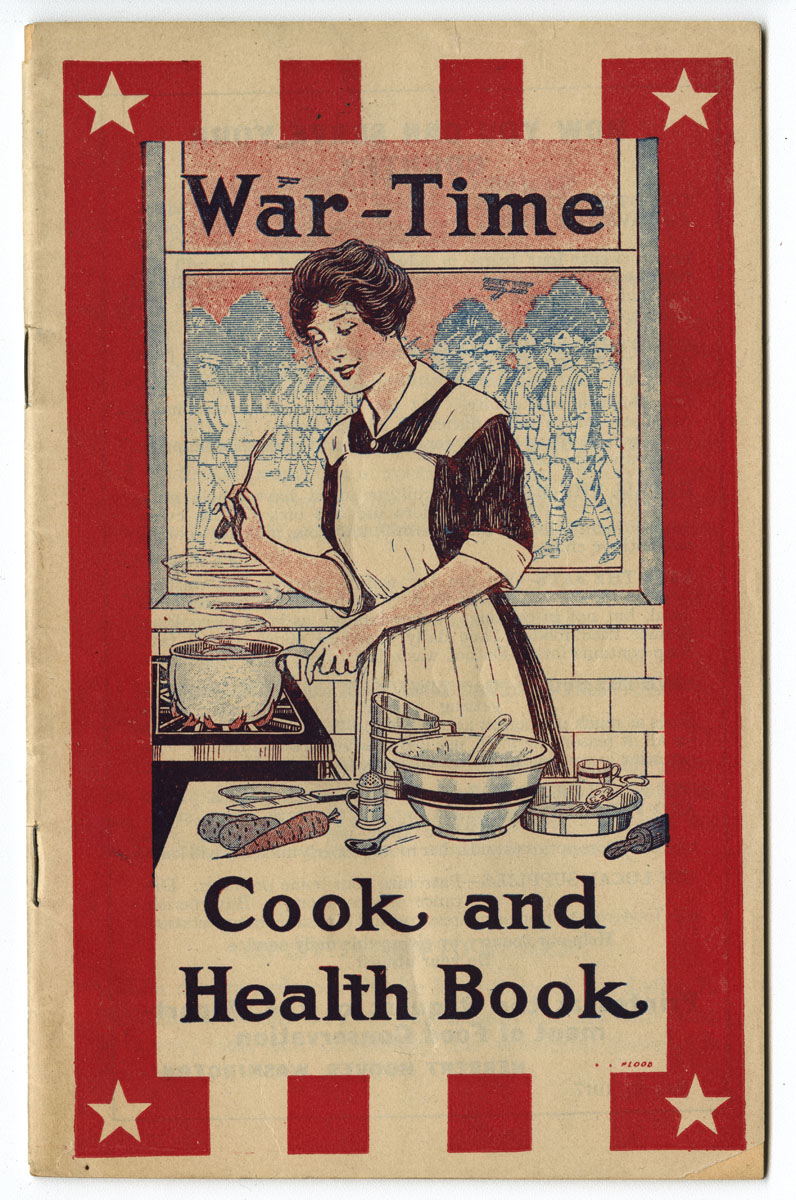

Lydia E. Pinkham Medicine Company, War-Time: Cook and Health Book (Lynn, MA, 1917). Gift of William H. Helfand.

How could every American serve their country? By monitoring what they ate. Lydia E. Pinkham’s Medicine Company supported food conservation by producing this booklet. Included are suggested menus with recipes with substitutions for meat, wheat, and sugar, such as bean loaf with tomato sauce, corn meal griddle cakes, and fruit salad with honey dressing (along with advertisements for their Vegetable Compound cure-all).

The Ladies’ Home Journal (October and December 1917; June and November 1918). Loan courtesy of Linda August.

United States Food Administration, Food Saving and Sharing (Garden City, 1918). Gift of Ellen Slack.

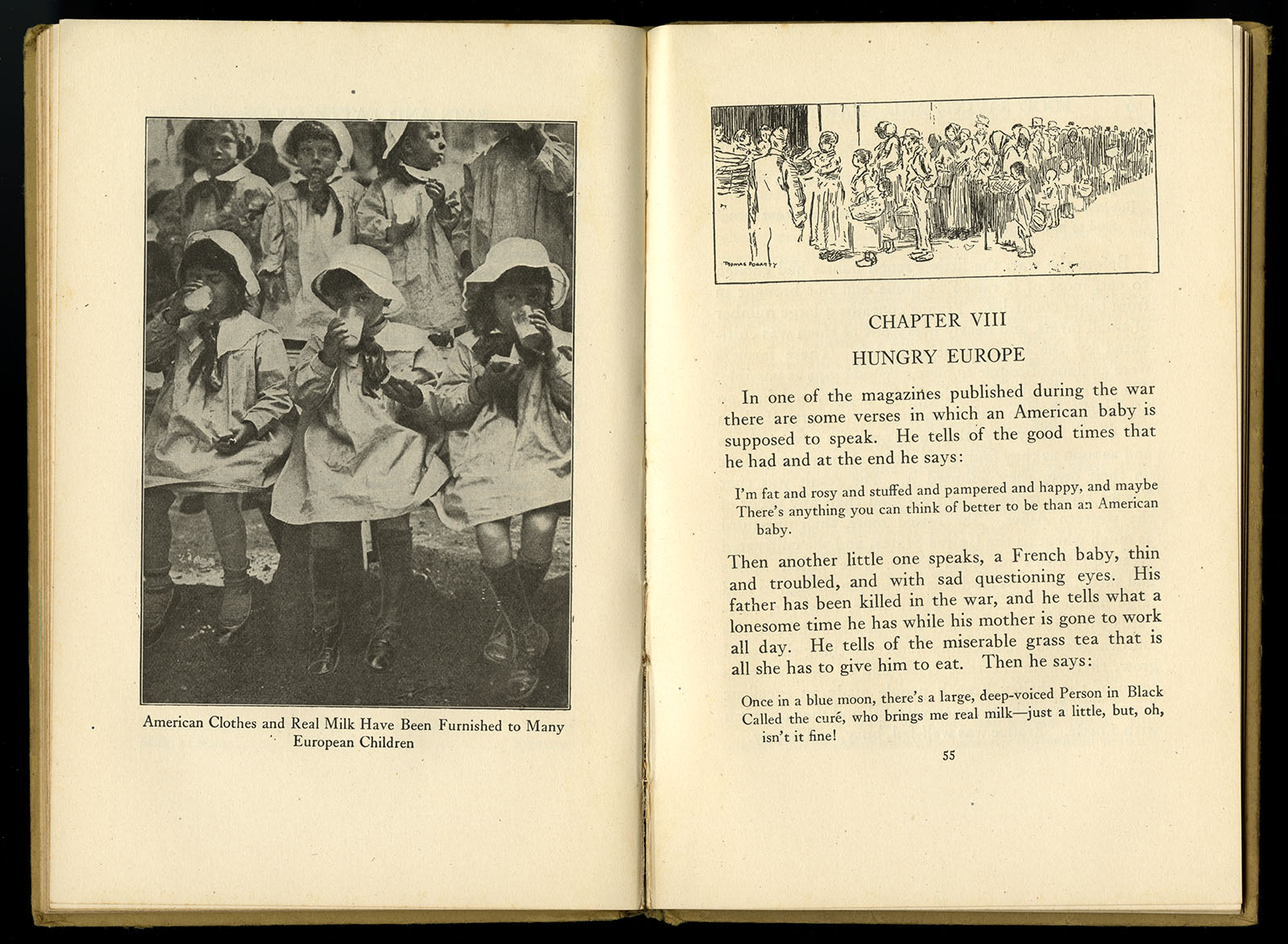

The Food Administration enlisted all Americans, including children, in food conservation. A food crisis wrecked Europe as farms turned into battlefields and farmers turned into soldiers. This publication, meant to be used in the classroom, illustrated Europe’s desperate need for food with photographs of orphans and bread lines. It contains information about what to eat, what substitutes to make, and basic nutrition. It ends with “U.S. means us,” a democratic appeal that each willing citizen must do their part.

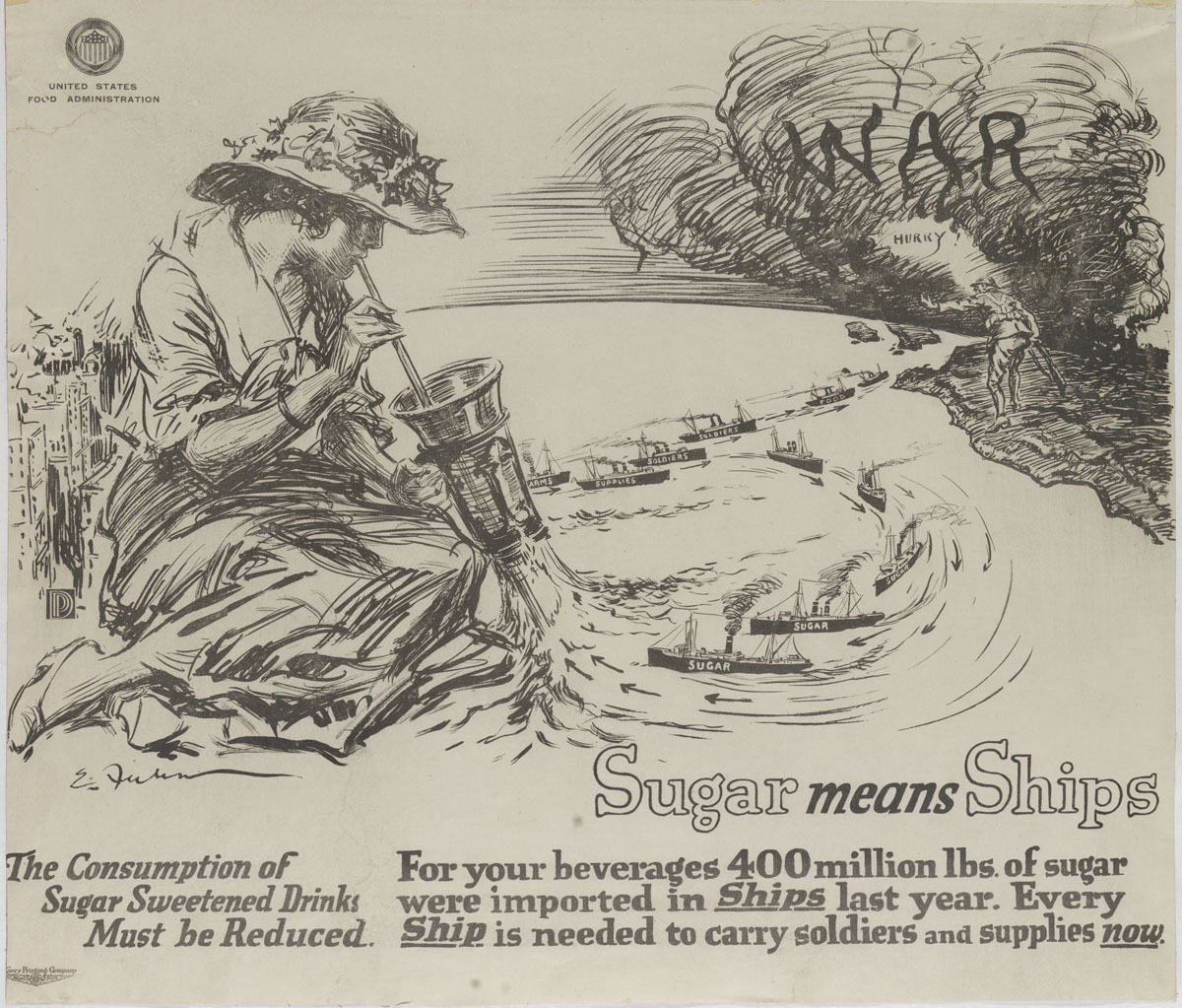

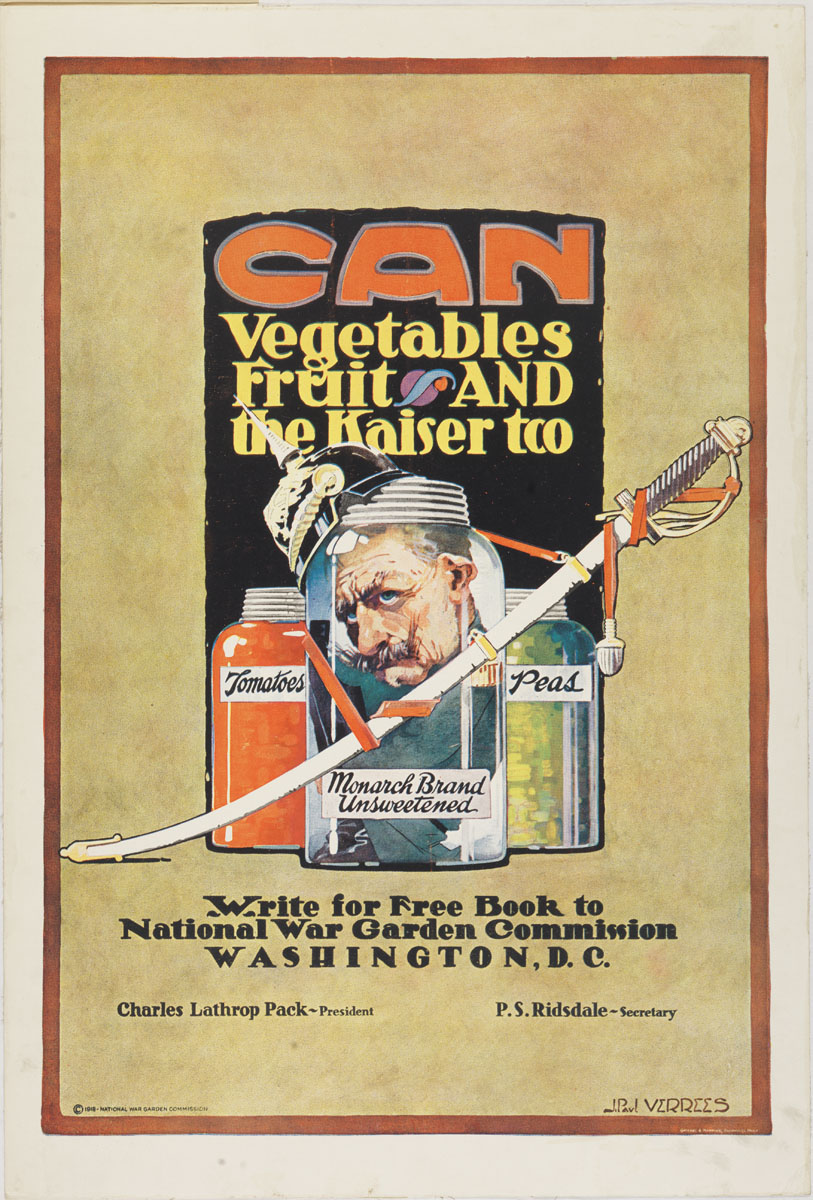

Ernest Fuhr, Sugar Means Ships (New York, 1917). Lithograph.

Conserving sugar not only ensured our troops had enough, but it also meant transportation would not be diverted from shipping arms and supplies to the front to provide for consumers’ needs. Each citizen had a patriotic duty to “do their share” to win the war.

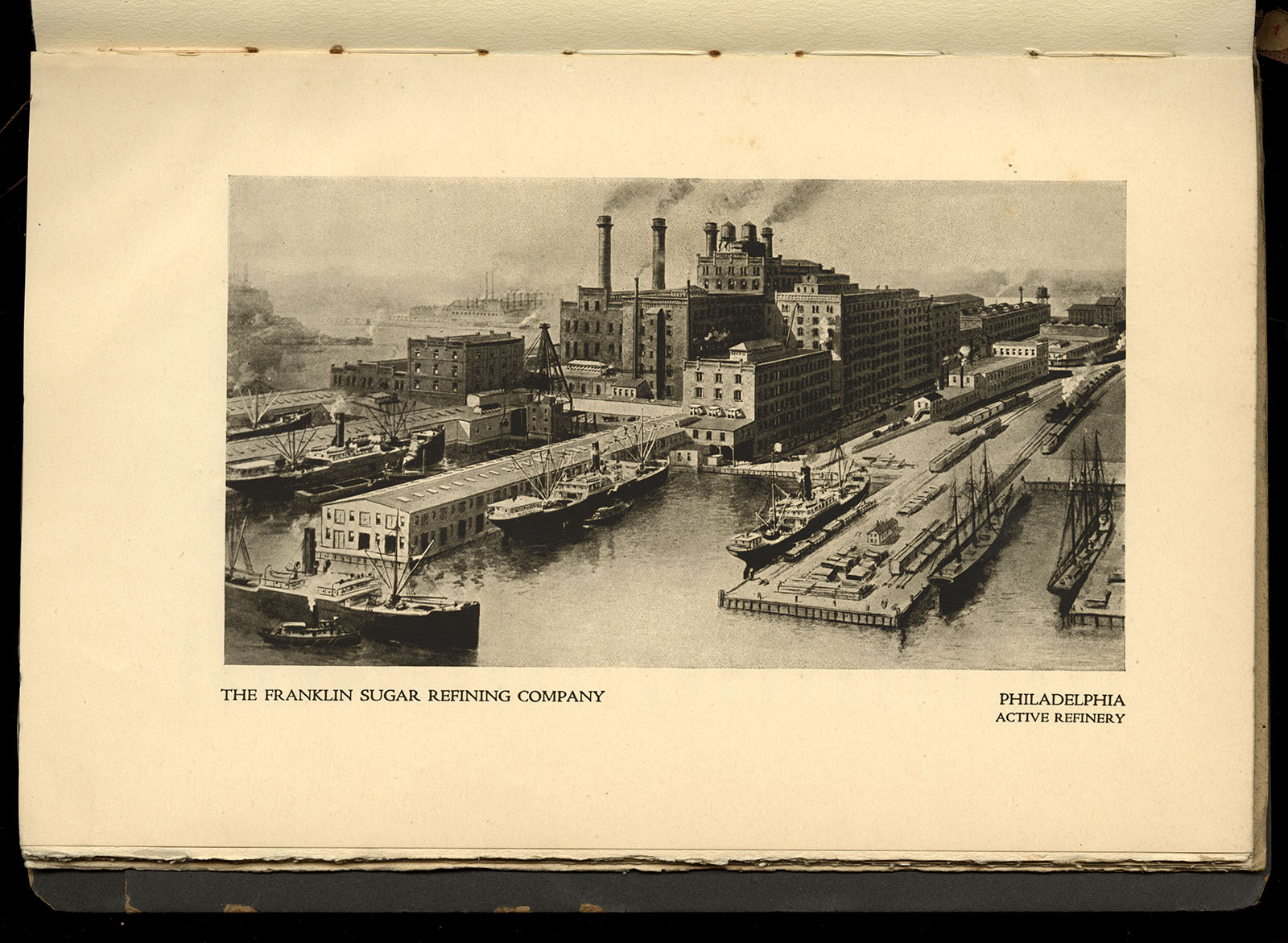

American Sugar Refining Company, A Century of Sugar Refining in the United States, 1816-1916 (New York, 1916). Gift of the author.

Sugar played a huge role in Philadelphia manufacturing. Large sugar refineries operated along the Delaware River. In 1915, Philadelphia had over 130 chocolate and candy manufacturers. Americans consumed much more sugar than our Allies, eating 85 pounds of sugar per person a year! In comparison, the British consumed 40 pounds, the French 37 pounds, and the Germans only 20 pounds.

Charles Pancoast, Photographs of Little Wakefield (Philadelphia, ca. 1918). Gelatin silver photographs.

Located in Germantown, “Little Wakefield” served as a demonstration center for the National League for Woman’s Service teaching women “if you cannot be a fighting soldier, be a farming soldieress.” They held classes in home economics and canning and preserving, grew fruits and vegetables, and cultivated bees. They produced peas, beans, corn, cabbage, peaches, and raspberries on four acres. Today it is a part of La Salle University as the St. Mutien’s Christian Brothers’ residence.